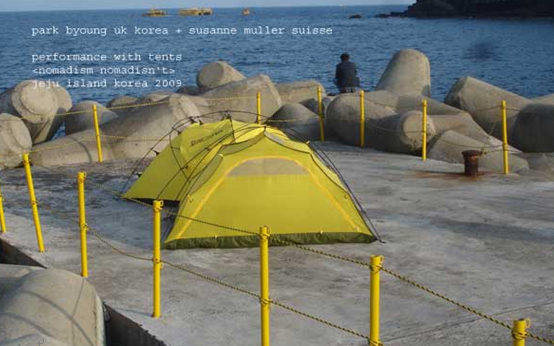

Nine Dragon Heads

ISLAND

15th~25th.APRIL.2009

Ali Bramwell. Channa Boon. Claudia Bell. Daniela de Magddalena. Harold de Bree. iliko Zautashvili.

John Lyall. Kim Nam Jin. Lee Seung Taek. Magda Guruli. Park Byoung Uk. Paul Donker Duyvis

Shin Yong Gu . Susanne Muller. Yoko Kajio . Yoo Joung Hye.

15thInternational Environment Art Symposium

Nine Dragon Heads 2009

Nine Dragon Heads makes an attempt and stimulation to leave better heritage in the future from the environmental and spiritual viewpoint. Human beings have repeated development with enormous domination and control about environment. There is no doubt that human beings are superior in every respect.

Thinking back to the past history, many species on the earth were exterminated because for some reason the friendly environment which helped their birth changed into hostile attitude. While mankind, the first species that had the ability of operating on surroundings, have got out of innumerable change of nature to some degree.

But human has regarded the nature as the target of challenge and conquest, that is to say, as the subject of testing mankind's ability in the process of transforming and possessing the nature.

Ultimately if we are asked a question when the mankind will disappear, we may answer "the day will not be far distant." No matter how peculiar men may be, we must deeply realize that men are also the product of appropriate environment and the part of huge nature. Can men lead a life with understanding and respect about the world of nature ?

Can men maintain a life peacefully and fairly for the long survival of mankind ? What decide this future of human is the mutual relation between human and human, human and circumstances.

NINE DRAGON HEADS changes close-minded 'I' into open-minded 'I' and urges to reconsider equilibrium relation between human and environment through the art holding in common human's infinite imagination, experience, and ideas. NINE DRAGON HEADS joins various culture and unfolds international composite art. We hope to have in common community consciousness and impulsion of the cooperation existed deeply in human's heart through these various forms. Human beings who have single species of Homo Sapiens Sapiens have developed wide and diverse culture. we understand that the diverse difference of culture is the speciality of culture itself, not comparison or superiority.

NINE DRAGON HEADS expects to have a new understanding of human nature and world through the art as long as men. We anticipate that we can leave healthier environment-the heritage of future-to posterity through the curable function of art.

" Later in the evening when the Island had fallen silent apart from the occasionally audible singing of the shaman and his colleagues down the way, as they attempted to entice the wayward spirit of someone who had fallen ill to return to the patient thus restoring her to health."

Every human being has a need to jump into

the unknown.

For some reasons some people do it, some people don't.

Fear for the unknown.

Fear the other part of our instinct is what

stops us.

We have a strong need to discover.

To go further than our father.

To go more West, to go more East ...

Discover the unknown sea, the unknown forest, the unknown desert, the unknown island.

The Island stands for

our desire, for mystery, isolation, safety and paradise.

All things that humans lack in daily life. The treasure is always hidden on the

An island is a piece of land that is surrounded by water.

The Island is inhabited by people who want to

escape the turmoil of the modern cities of the mainland with quickly changing

lifestyles, cultures, rigid ethics and aesthetics.

The inhabitant of Islands

are often sincere keepers of traditions, myths, legends.

Usually they live moderately.

An amazing example was the discovery of a famous book

- The Edda - the Icelandic medieval manuscript Codex Regius ('The King's

Manuscript'). The Edda kept the forgotten stories of Northern European mythology

and Germanic heroic legends. The Christian Church and fundamentalist

missionaries had done their work properly. Almost all the cultural heritage of

pre-Christian wisdom, science,culture, religion, literature, music, dance and

art was wiped out.

A whole continent brainwashed completely. The earth

became flat in every sense. Thanks to the remoteness of the island Iceland we have

a bit of our ancestors memories back.

A similar thing happened in