|

Nine Dragon Heads at

the SarajevoWinter2006

|

|

|

The Sarajevo Winter Festival (Sarajevska Zima) has been running

continuously since 1984, when it was founded as an adjunct event to the

Sarajevo Winter Olympics. It has

continued every year, including during the war, which began on April 6th

1992, when Serb militants opened fire on thousands of peace demonstrators in Sarajevo, killing at

least five and wounding 30. The siege

continued until October 1995, the longest city siege in history. We heard stories of people ducking sniper

fire on their way to festival venues.

There are bullet holes in Festival Director Ibrahim Spahic’s office

walls; shrapnel in his head, we were told. With this history of incredible

defiance and commitment, Sarajevo’s annual arts,

jazz and film festivals are now some of the major cultural events in Eastern Europe.

|

Artists from throughout

the world travel there to participate, and to enjoy the warm hospitality of the

people of Sarajevo. At the same time,

visitors new to this pretty city observe evidences of ravages of war. They no longer experience what Susan Sontag

described when she directed Waiting for

Godot at the fetsival: ‘Bombs went off, bullets flew past my head.... There

was no food, no electricity, no running water, no mail, no telephone, day after

day, week after week, month after month.’

Sontag explains that the

continuance of arts activities during the war as a ‘serious expression of

normality’. Evidence and stories of

those hardships, and worse, still abound. In the very first hour of one’s

visit, one sees that this is a city of new cemeteries. Pristine white marble

tombstones are present everywhere one looks, in areas that were once the city’s

parks.

|

|

Postcard 1abelled ‘1992 Sarajevo 2002’. Purchased in Sarajevo.

|

This is indeed sobering for the visitor from a

distant place; visitors who knew about the genocide, because they saw it on

television. That mass exposure did not mean the world could stop it. In our distant countries we saw scenes of

Europeans starving behind barbed wire, disturbingly like 1945 all over again.

The dreadful term ‘ethnic cleansing’ entered everyday language.

|

For artists attending the

winter arts festival in February 2006, the highly apparent physical residues of

war on the cityscape – the cemeteries, bullet holes in the facades of

buildings, demolition sites, even postcards of war scenes - were a raw and immediate form of

consciousness-raising

|

|

Internationalism

The 2006 official Sarajevska Zima catalogue was in excess

of 200 pages, indicating the vast scale and range of this event: musical

theatre, puppeteers, photographers, musicians, singers, dancers, video

installations, tableau vivant, city illuminations, events for children. Nine Dragon Heads was just one group of the many who

participated in the festival in 2006.

|

Nine Dragon Heads is a changing group of artists, co-ordinated by Park Byoung Uk

(Korea) The emphasis in this group is on the

internationalism of their work; for most of this group, it would be difficult

to identity their country of origin by their work.

|

|

|

The 2006 Nine Dragon Heads group included artists from places

as diverse as Bosnia-Herzogovnia, Turkey, Japan,

Korea, Australia, New

Zealand, Switzerland

and Norfolk Island. All of these artists have

traveled and worked in various countries; their work is documented in a wide

range of international texts. Most have websites featuring their work. There

has never been a time in history

when artists could be as international.

|

Artists in the city – creating spectacles

Nine Dragon Heads held their exhibition at the Turkish Cultural Centre on Mula

Mustafe Baseskije for one week, February 8th - 14th

2006. For some of the artists, their

work in this show was their sole outing at this festival.

|

|

Joung-Hye Yoo (Korea) created a wall installation of small

colorful raffia flower-like pieces in bright orange and yellow: a radiant

blossoming of nature/ culture from elsewhere, flourishing in the bleak Sarajevo winter.

|

|

|

Bedri Baykem’s (Turkey)

photographs of himself as Natural Man crawling naked amongst beach debris on a

lake edge in Korea

also recalled another place and climate, far away. His work could be read as

comment on the anti-conservation ‘achievements’ of human evolution.

|

|

Ichi Ikeda (Japan)

reiterated this theme in his political and environmental concerns for water

preservation. His work is famous for its elegant depiction of water as a

fragile consumable: a natural resource that has become a commodity. Here he exhibited a wall montage of large black

and white photographs of water running through the hands of people trying,

impossibly, to hold it; and an

installation of soil, tubing and fresh water, referring to the depletion of

this precious life source. His work invites not just reflection, but

also urgent political action to ensure its future availability.

|

|

In a different vein,

Jusuf Hadzifejzovic (Bosnia

-Herzogovnia) presented a performance about escape from darkness: the confined

body blinded by its enclosure – a colorful plastic bag – and forced to poke its

way out into the light. The drama of

this piece’s reference to imprisonment was poignant expression of the

conditions the citizens of this country endured during the war: under siege in

their own homes, wondering when and how there could possibly be a way out.

|

At the same time the materiality of this work – a simple plastic

bag - pointed to the everyday nature of the scope for such enclosing of people:

high-end technology is not necessary for

extreme cruelty. (We recall the use of simple

box-cutters as lethal weapons in the September 11th attacks). Hadsifejzovic’s escape was also a bursting

from the bag of his own forceful artistic personality: a dynamic metaphor for

the positive character of the city of Sarajevo

itself, which utilized the arts as an expression of refusal to be confined

during the war.

|

|

Some of the artists

stayed in Sarajevo

for at least another week, to participate in the festival and to make work in

the city and its environs. This was the

making of work outside the gallery; or entire city as gallery. The Nine Dragons Heads artists were not frivolous

tourists. They took very seriously this opportunity to engage with the city; to

be part of the normality of a city which did, after all, host this festival for

several years before the war.

|

Most of the group had not

planned their specific outdoor works before the festival; they had waited to

explore the city to locate suitable sites. There was also a day at the Sarajevo

Winter Olympic ski-field, to make art during a major snowboarding competition.

|

|

|

Swiss installation artist

and videographer Susanne Muller explained that she liked to search for voids,

and make the otherwise un-noticed spaces in a city into a visual event. ‘We can

never know every part of a city, even our own city’. She brought with her to Sarajevo lightweight tent

frames, and then searched locally for materials to make the tents’ canopies. A

second-hand shop near the Turkish Cultural Centre yielded plenty of used cotton

sheets. She installed one tent in the Nine Dragon Heads exhibition at the Turkish Cultural

Centre, where inside the tent flaps a television monitor ran a continuous loop

of 24 –frames-per-second.

|

The content featured

recent floods in Switzerland,

particularly near her home city of Bern:

a local catastrophe beamed out to the world.

This poignant inversion of shelter, the cataclysm inside the totally

unfunctional tent, sat in the context of the reparation of the houses and

public buildings of Sarajevo.

|

A few days later another

of her tents appeared in the burnt-out shell of the Hotel Europa. Through the former window spaces of this

demolition site, her brave little tent sat in the snow, an apparent shelter for

survivors of the 1990s siege. A few days

later Mustafa Skolpjak (Bosnia

and Herzogovnia) placed large cutout figures in the empty window frames.

|

The derelict hotel was

now inhabited once again.

Muller’s work was a timely echo of another tent site in the city.

|

|

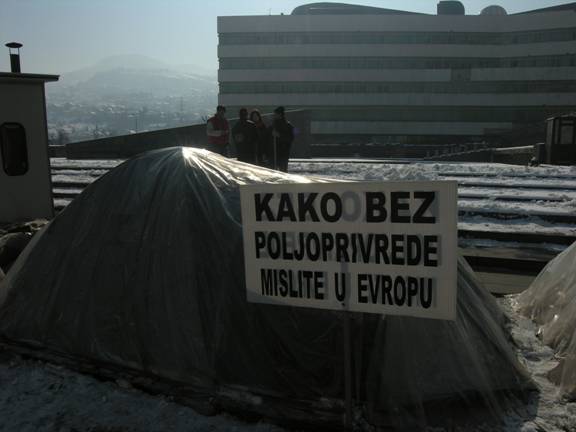

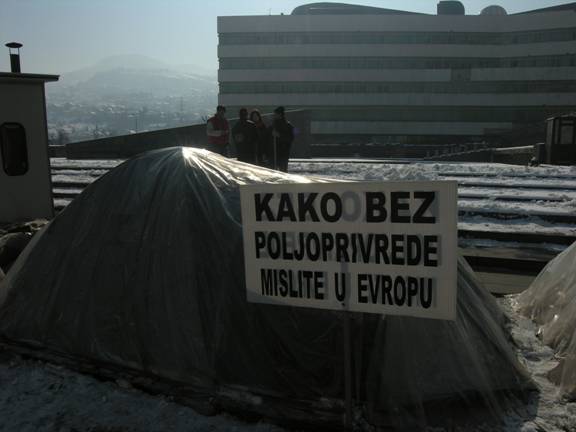

Part of the protest camp

of agricultural workers near the National

Museum.

|

On Marsala Tito near

the National Museum agricultural workers had been

camping for 235 days, in protest against the lack of government support for

agriculture. Their tents were on low

platforms in the snow. Despite lack of language in common, by showing them her

Visiting Artist tag and footage of her work on her video camera, she was able

to convey to them her solidarity with their cause. They laughed and indicated their own small

‘Olympic flame,’ and a great pile of firewood.

They handed out sweets. Muller

was invited to do an installation that included their tents, in situ.

|

|

|

|

John Lyall and de-nature

myth.

|

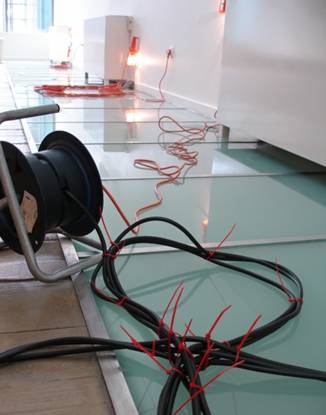

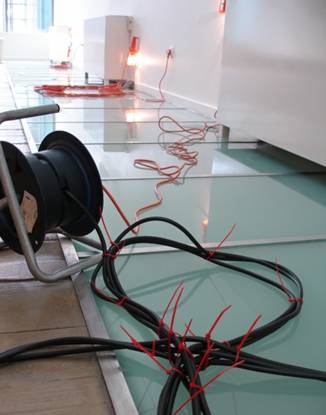

Meanwhile at Basčarsija John Lyall (New Zealand)

threw seed to the pigeons, hoping they would arrange themselves in the

formations of the marks he was trying to make with the grain. The pigeons would

not co-operate, but quickly ate the grain.

People seated outside the cafes watched as the pigeons engulfed him. His

marks without the pigeons were more successful: Cartesian swirls foot-printed

into the snow at Basčarsija and at Vogosca, which

remained visible for several days, and aroused local curiosity. The elegance of

these shapes echoed his work in the Nine Dragon Heads

gallery exhibition: the same mathematical curves assembled from orange and

black extension leads, with inspection lamps shining onto sheets of New Zealand

native paua shell (iris haliotis). In his gallery performance piece the

same curves appeared as cut-outs of postcards, the perforations heavily

outlined in lipstick, as in ‘sent with love from…’

|

He also became a fixture wandering

around the town with two helium inflated animals bought from street

sellers: a feral tiger and leopard. They stared at sumptuous fur coats in shop

windows; they bobbed against the formal framed photographs of Marshal Tito,

décor at Tito Café. They were finally

released into the Miljacka

River, where they swirled

about in the weirs, only to be eventually washed up on the frosty shore: a foreign environment indeed for these two

stray lost creatures.

|

|

|

Miles Sanderson from Norfolk

Island installed fruit –

large luscious oranges – as regularly spaced architectural motifs along

the bridge famous as the location of the assassination of Archduke Franz

Ferdinand. As in his gallery

work, a drift of rolled paper sea anemones, his emphasis was on order,

symmetry, and surprise achieved by using simple, readily available materials.

The fruit glowed in the dim wintry afternoon mist. Gypsy children hung about, waiting for the

artist to finish, and maybe give them the oranges.

|

Sanderson reflected on this later. ‘I won’t use food again

in an installation in a place where people cannot afford fruit’. In a later work, at the ski-field of the 1984

Sarajevo Winter Olympics, he used red string to make marks in the snow, and to

tie around winter twigs that poked up through the ice crystals. The quiet elegance the red streaks on the

shimmering white ground was respectfully resonant of blood in the snow, a

tribute to the lives lost throughout this region during the war. We’d all seen the ‘roses of Sarajevo’, indentations from the

explosion of mortar shells on the city’s pavements, filled with red concrete in

remembrance of those killed.

|

|

Video still: Ali Bramwell

walks her sawn through the streets of Sarajevo.

|

Meanwhile at the ski-field Ali Bramwell

(New Zealand)

laboured hard to turn snow into a large swan. Her life-sized swan, layers of

corrugated cardboard stabbed with metal shafts, reposed on a gently-lit ledge

in the Turkish Cultural Centre gallery.

It referenced silent tales of migration, while inferring all those

mythic, figurative and mystical cultural references to swans; and the current

global alarm and doom-saying about Avian flu, predominant in news broadcasts

that week. Would this disease be the

next apocalypse? Would it strike this

city, too, still recovering from another disaster?

|

Ali Bramwell took her swan for a walk around the streets of Sarajevo.

|

In Svetlost Park

the work took its final form, ‘Walking with swan: stone sleeper.’ Bramwell describes this walk:

|

‘It began at the bust of Mak

Dizdar (Bosnian poet) and ended at the National Museum.

The Swan (labud) was bolted together from cardboard cartons collected in the

city, in itself a different kind of document, a kind of stored history in both

material (used boxes stamped and labelled) and form (the image of swan is

overlaid with many layers of poetic and mythic history). I placed the swan

beside Dizdar. For the walking performance I tied the swan to my body with 9

metres of black satin ribbon, wrapped around and around my chest and walked

dragging it trailing behind me. It took just over half an hour to walk the

distance.’

|

|

Consummate performer

Park Byoung-Uk’s

irrepressibility was a constant motif during the weeks the Nine Dragon Heads

group worked in Sarajevo. At the ski-field, once snowboarding

competition had finished, Park raced beneath the banner labeled ‘Finishing

Line’ and threw himself in the snow. In his arms he clutched the handmade sign

he carried on behalf of fellow Nine Dragon Heads

artist, Bedri Baykam, ‘Yes sir, I know

you’re very special’. As one of the

founders of Nine Dragon Heads, he

has delivered artists over and again to venues throughout the world. For him,

performing as an artist is also about facilitating the performance of others.

|

|

Park’s medium is the everyday actions

of people in nature, going about their lives. His fluorescent orange jumpsuit

foregrounds the artist, the brand Park Byoung-Uk. But once he has donned this garment, his actions in the social context are so

everyday and perfectly positioned within the actually quotidian of others, that

he simply appears to be a municipal official, or an official organizer – a

trenchant wit that translates remarkably across cultures.

|

Performing

in Sarajevo – the joy of participation

|

Whatever distance they had traveled and

however different their own cultures from the everyday life they experienced or

observed in Sarajevo, these artists could not be oblivious to the context in

which they found themselves. Here was a city where the citizens had survived

unimaginable nightmares in recent memory.

It is still addressing issues of survival. At the same time,

here was city with sufficient support from citizens and government to stage

several ambitious annual festivals.

|

|

The artists installing objects and

performing events in the city contributed to the festive feel of Sarajevo in wintry

February. They invited a genuine

democracy of viewer participation and enjoyment, unfettered by any need for

formal aesthetic sanction on visual pleasure.

|

Sarajevo’s icy streets became galleries of inclusion, not exclusion.

The artists’ works in the square, on the bridge, in the river, at a derelict

hotel, in any void Suzanne Muller could find, were public presentations for

anyone who cared to look. Indeed, this

invitation to artists to make work anywhere in the city may be seen as a graphic counter to the

alienation of art in many city galleries all over the world, where the

immaculate intimidating hushed white

spaces are irrelevant to perpetual non-visitors. The street and ski-field works

bore no inherent sense of the sacred or precious, no suggestion that one must

have some elusive insider prior knowledge to read these presentations. The artists were creating blatant spectacles

for every single person passing by.

|