Fishlight, 1990, mixed media.

|

Fishlight, 1990, exhibited at his graduation exhibition, an internally lit polyester cone emerges from the ceiling. By installing it in the ceiling a tension was created in the vertical space between the open and closed cones. On the open cone form underneath, dried fish from Suriname were attached to the metal and faced upwards towards the light. Their upwards direction not only illustrated fish being attracted and then caught (as fish are when fishing at night) but symbolise migration (in this instance, Surinamese culture being attracted to and influenced by western (Dutch) culture). This theme of west verses non-west was further emphasised by use of the materials (industrial polyester in the cone above and smelly dried (natural) fish below) and lighting (the cone above illuminates the cone beneath). It was intended to be light-hearted and serious in its reference to the 'west-rest' world power relations and myopic views.

The Material Paintings, 1991 - 92

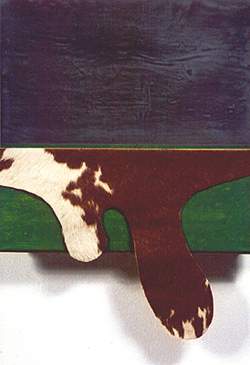

Jessy made a series of paintings in which paint was only used when it was necessary. For example in, 'The white cliffs of Dover (and the blood-stained coast)' a layer of lead covered the lower half of the painting while the top half was painted in flat colours; blue for the sky, a green triangle for the grass, white for the cliffs and a fine red line (for the blood). Attached to the painting on the left was a piano lamp facing inwards so that it caused a reflection of the bulb on the blue (for the moon) and on the lead (for the moon's shadow). All North European seas are grey, so lead was perfect as a metaphor for the sea. Jessy's use of lead for the sea was influenced by Kounellis's telling him that the whole atmosphere here in northern Europe is absorbed in greys, in contrast with southern Europe. In 'Dutch Landscape', Jessy used a strip of lead to symbolise the sky over the flat, green land and then over this laid a piece of fur, symbolising the livestock on the land. Our flat land...

|

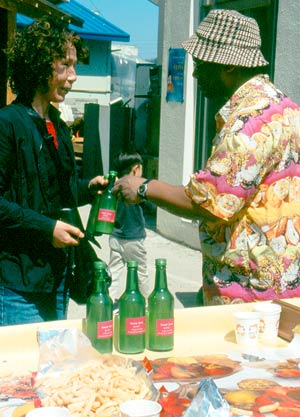

Sculpture by Jessy Rahman and other art students, 1988.

Sculpture by Jessy Rahman and other art students, 1988.

Hommage to Joseph Beuys,

Hommage to Joseph Beuys,

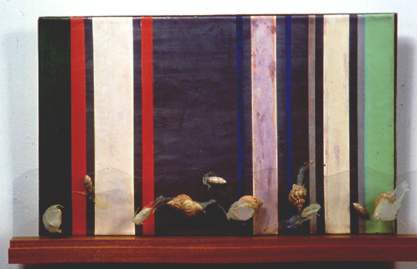

Over the ocean and over the seas, 1992, lead, paint,

Over the ocean and over the seas, 1992, lead, paint,

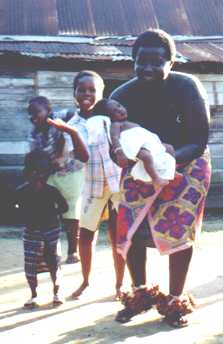

Children dancing variations of the Awasa dance,

Children dancing variations of the Awasa dance,